Exercise 1

Allow at least 2 1/2 hours for all of Exercise 1, dependant on available hardware

Part A: Introduction

The aim of this teaching resource is to introduce you to the technical basics and the theoretical issues underlying the process of creating digital reconstructions of archaeological sites. As will become apparent throughout the module, certain elements of the actual workflow are very project-specific and contingent on the needs of the project. To frame your thinking and the decisions you make in the following exercises, we have provided an example ‘Project Brief’ below.

The Project Brief: Develop a scaled digital 3D reconstruction of the structures on the site of Malthi to help researchers and the general public to better understand its layout and how this impacted the settlement’s inhabitants and their movement within the site. Due to the complexity of the standing remains, 3D laser scans of the site, archived with SPARC, will form the ‘foundation’ for the site reconstruction to ensure the spatial relationships between structures are metrically accurate. This reconstruction may be used as the groundwork for creating more detailed hypothetical interpretations for wider distribution.

If we break down the project brief into separate tasks and outputs as a short outline to frame your ‘Design Document’ (which you will build on later), we can see that it necessitates certain key skills and considerations:

-

Assess the various archived files and 3D resources for quality and relevance to the project aims;

-

Prepare archived laser scan data so that it is usable in 3D modelling software;

-

Evaluate software tools to identify those best suited to building and delivering the reconstruction;

-

Outputs:

a. A reconstruction built on the laser scan data that represents one possible interpretation for the Malthi settlement, prioritising accurate spatial layout and movement;

i. Ideally presented in a way that allows basic navigation of the site.b. Archive in an accessible and reusable format for potential reuse at a later date;

i. Record and compile appropriate paradata and metadata to accompany the reconstruction in the archive.

Though you would normally be working with a diverse team of specialists, the exercises will prioritise learning about the technical workflow and theoretical background specific to the role of 3D reconstruction artist. In the first exercise, though each of these steps are intrinsically linked, we will cover the first three points as a ‘pre-project planning’ and data assessment phase. We will then discuss the process of working within a team, how to decide on the appearance of structural elements not found in the archaeological record, and how to choose between the variety of 3D modelling software to create reconstructed assets in Exercise 2. Step 4a will be covered in Exercise 3 and 4, as we consider the process of optimisation of 3D assets and the generation of new assets to illustrate the reconstruction. Exercise 5 will address Step 4ai, where you will evaluate Sketchfab and Unity for their suitability to accomplish the research aims. Finally, optional resources outline the appropriate methods of archival for reconstruction projects and the associated paradata and metadata will be presented and discussed.

Preparation – Key Considerations Before Undertaking a Digital Reconstruction of a Monument, Urban or Rural place

There are a number of practical and intellectual considerations that need to be addressed before undertaking a digital reconstruction of an archaeological site or monument. While many of the following points would be made explicit through a more detailed project brief, it is important to ensure that these are clear from the outset to create a successful digital reconstruction. In general, these will help you assemble the information you need before going into an initial collaborative meeting:

-

What are the aims/purpose of the reconstruction? Who is the audience? Who are the stakeholders? What afterlives might the reconstruction have?

-

What is the quality and character of the 3D laser scan or photogrammetric data available? What datasets are required to fully address the aims of the reconstruction? Does it need to be metrically accurate? How do you assess the quality of the available 3D datasets; what level of detail is needed for the reconstruction (Exercise 1)?

-

Which software tools are suitable to employ in the project? How do you critically evaluate software tools for a specific purpose (Exercise 2)?

-

How much time is available to complete the project? How to prioritise different aspects and manage expectations (Exercise 2)?

-

What additional functionality would need to be built in to successfully address the aims of the reconstruction? How will you denote ambiguity – will this be depicted differently than ‘certainty’? Will multiple phases of the site be included (Exercises 2 - 5)?

-

When recording paradata (Paradata is a record of the decisions made and your thought processes for including or excluding certain elements), what level of detail will you document? How will you characterise your workflow? What format will this take in the final output and archive (Reflect Further materials)?

By ensuring that these are fully considered before an initial meeting with your collaborators, you will be prepared to ask more specific questions and have a more productive first meeting.

These considerations are complicated, as they are often underpinned by a combination of practical and intellectual issues that require different skillsets to address. The theoretical concepts will be summarised and offset from the practical considerations in call out boxes.

What are the aims/purpose of the reconstruction?

As suggested above, while the aims or purpose of a digital reconstruction should ideally be defined from the outset in the project brief, this may need fuller consideration, as this will impact almost all of the other choices to be made in the project. In archaeology, there could be many purposes for digitally reconstructing a site, though some are more frequently employed than others. There are two main ‘types’ that digital archaeological reconstructions tend to fall under:

- Curated public-oriented interpretation with at least some emphasis on visual aesthetics, either for delivery via VR, AR, or online delivery (games, 2D or 3D, video or flythrough; includes museum installations)

- Information-laden for other specialists/archaeologists; can be used as a tool to develop interpretations through their working process (GIS/layered interface, multiple phases, multiple interpretations of possible construction of structures)

However, it is important to note that these types are not necessarily mutually exclusive; in some cases, feasible interpretations may be tested by archaeologists and illustrators in a Type 2 reconstruction behind the scenes, but what reaches the public is a curated, more manageable Type 1 reconstruction. It is essential to identify what type of digital reconstruction your project is aiming to produce, as this has implications throughout.

Note: These are not the only distinctions that can be made between types of digital archaeological reconstructions. For further reading, see Lanjouw 2016 and Pujol-Tost 2007 in the bibliography below.

What is the quality and character of the 3D laser scan or photogrammetric data available?

One aim of this teaching resource is to demonstrate how SPARC’s legacy 3D datasets can be reused to create meaningful digital reconstructions of archaeological sites. However, it is important to recognise that a digital reconstruction of an archaeological site does not necessarily require 3D datasets recorded directly from the extant archaeological remains, like those generated from methods like laser scans or photogrammetry.

Whether existing laser scan or photogrammetric data will be useful in a reconstruction will depend entirely on what the aim of the reconstruction is. If the aim of the reconstruction is to give viewers a sense of what it was like to live on a site in the past, it can be more effective to allow a digital artist to generate the environs, structures, and material culture from drawings of past excavations, recovered artefacts, or old drawings and maps (in the case of historical structures where such records exist). This was the case for Smart History’s ‘Edinburgh 1544’ project.

However, there are a number of reasons why it would be valuable to incorporate metrically accurate 3D data recorded directly from the archaeological site into a digital reconstruction.

- If you wish to create an Augmented Reality experience, it would be easier to align the reconstruction with the existing standing remains based on shape recognition if accurate scans were incorporated into the reconstruction.

- If you are using the process of reconstruction to explore potential interpretations alongside an archaeologist, spatial relationships between structures and a sense of scale may be particularly key to understanding how a now-incomplete space could have been used.

- Taking measurements may be necessary to make more specific comparisons between different elements of a site, especially if the reconstruction incorporates information from multiple field seasons (Wilhelmson and Dell’Unto 2015).

In the case of Malthi, the layout of the standing remains is complex, so building the reconstruction from the 3D scans will be particularly useful in understanding the spatial layout of the site and how its occupants would have navigated it.

Note: While there are a number of justifications for utilising 3D datasets recorded from real world remains, there are other considerations to take into account. One of the primary issues repeated in almost all of the relevant literature is the concern that archaeological reconstructions must not be misleading in the way that uncertain elements are incorporated in the final output, as digital reconstructions are perceived as authoritative statements. The London Charter for the Computer-based Visualisation of Cultural Heritage highlights this as well through Principle 3 in particular, as it states ‘to ensure the intellectual integrity of computer-based visualisation methods and outcomes, relevant research sources should be identified and evaluated in a structured and documented way (London Charter 2009, 7).’ The inclusion of data recorded directly from the site, which is often photorealistic, retains an additional layer of authenticity that ‘could be more convincing than a “scientific” non-realistic reconstruction (Forte 2014, 114).’ What makes a digital entity ‘authentic’ is complicated to fully define, especially in the digital sphere (Jeffrey 2015), and because an individual’s cultural background will influence one’s perception of ‘authentic’ (Forte 2014, 114). While it is still unclear how the incorporation of photorealism affects an audience’s perception of a digital reconstruction and its authenticity, some research has suggested that there is an expectation from the public that digital reconstructions are the final or authoritative interpretation of a site (Drettakis et al 2007, 17; Watterson 2015, 126).

With these implications in mind, the modeller will need to decide whether their additions/alterations to the laser scan data will also be given a photorealistic texture or if uncertainty in the reconstruction will be depicted in a different way (ie. unrealistic colours in the given context or different levels of transparency). However these issues will be addressed more fully in Exercise 2 when discussing paradata.}

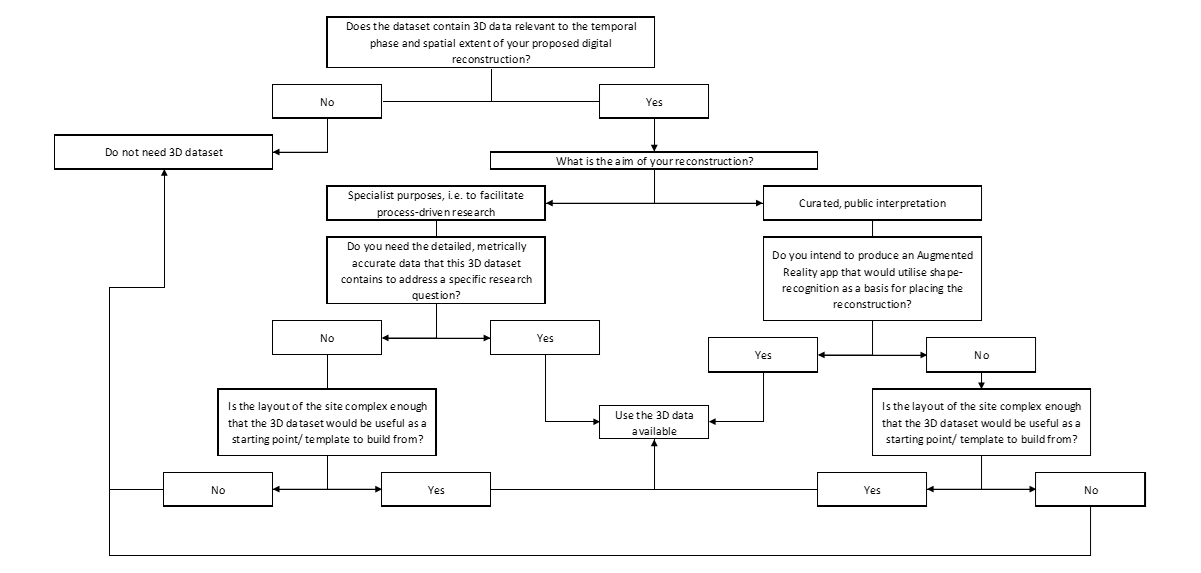

Think and Respond: Take a look at the ‘Decision Tree’ below – can you think of any other instances in which you should use the laser scan data rather than building the 3D reconstruction from other resources?

| Back to the Introduction | Continue To Exercise 1 Part B |